Goethe’s Living-Nature Imagination

By Dennis Klocek 23 min read

Dennis Klocek and Joel Morrow, Drawings by Famke Zonneveld.

First published in Biodynamics, Spring 1985 #154

“An eternal living activity works to create anew what has been created, lest it entrench itself in rigidity.”

from Goethe’s poem “One in All”

“The phenomena of formation and transformation had taken a mighty hold on me; here Nature and the power of imagination seemed to be vying with one another to see which could prevail with greater boldness and to greater lengths.”

from Goethe’s “Genesis of the Essay on the Metamorphosis of Plants”

Those who have tried to grasp and not merely read about the nature-consciousness developed in Goethe, know how elusive this child of the 18th century can be. For no sooner do you grasp what appears to be a limb (or branch), then at once the fragile form disappears. You hold in your hand something akin to the carbon structure of the thing or a burnt etching, but the living experience awaits the next effort of perception. What is missing from all these pursuits is often the realization that the act of disappearance is the creature itself. It calls forth in us almost like a gift from nature her own power of transformation, which fights actively against human rigidity in all its aspects.

Goethe himself realized that the mind would have to acquire a mobility akin to the power of growth in order to grasp the progression of forms in nature. In his essay on “Intuitive Judgement,” he writes:

“Through contemplation of ever-creative Nature, we might make ourselves worthy of participating intellectually in her productions.”

To Goethe this was an extension of his artistic imagination, but with a significant difference. He agreed with Heinroth’s characterization of his nature-imagination as “objectively active.” In other words, his picture of nature’s formative activity only arises inwardly in response to an actual sequence of growth-forms.

“By this he [Heinroth] means that my thinking is never divorced from objects and that the elements of the objects and my observation of them inter-penetrate my observation is itself thinking and my thinking IS a way of observation.”

Another contemporary of Goethe’s, Wilhelm von Schutz, also characterized this inner development:

- Firstly, “whatever Goethe looked upon in nature immediately acquired the character of a living experience for him.”

- Secondly, his “treatment and arrangement transforms nature into wonderful fragments of infinite wholes.”

- Thirdly, “originality of content sets the work apart from all previous contemplative observation(s) of nature.”

- And lastly, with Goethe “the inner and outer worlds are more closely united than in other minds.”

Perceptual Schooling

Because these qualities developed in Goethe are so close to those needed to understand nature today, we would like to dwell on a few scenes from Goethe’s perceptual schooling.

One of the first books available to Goethe was a primer called Orbis Pictus Sensualem (“Pictures for the world of the Senses”) by Amos Comenius. Goethe says, in his Autobiography, that this was the only book available to him that was specially written for children. It was based on a new educational stream whose goal was to awaken the immediacy of the senses using “observational instruction.” Ironically, it was written in the dead language of Latin. Like the old Roman Year-God, it had two faces, one looking into the past, the other into the future. The primer taught young children to draw the plants and animals they saw in nature and to learn to imitate the songs of the birds and the calls of the beasts. Comenius sought to lead the unfolding mind of the child into the sense world in an imaginative and yet ordered way. Goethe also says that he was fascinated by the pictures of transformation he found in Ovid’s Metamorphoses and studied them avidly. From the very beginning, he remembers being steeped in the impulse to understand the world through images that were mobile enough to reflect reality.

In his autobiography, Goethe describes himself, as a small child, having a distinct foretaste of the nature-imagination that was to shape his life. This arose like an active contradiction to his staid, classical, bourgeois upbringing. At about six years old he built an altar he says, to “the God of Nature:”

“The God who stands in immediate connection with nature, and owns and loves it as his work seemed to [the boy] the proper God, who might be brought into closer relationship with man, as of the motion of the stars, the days and seasons, the animals and plants. The boy could ascribe no form to this Being: he therefore sought him in his works and would, in the Old Testament fashion, build him an altar. Natural productions were set forth as images of the world over which a flame was to burn, signifying the aspirations of the human heart toward its maker”

Goethe’s youthful intimations were somewhat dampened when the magnifying glass which he used to ignite the altar incense with the first light of dawn also burned his father’s valuable music stand!

Goethe began to draw from Nature already in his youth. His observation of form was greatly aided by working with the German painting master Peter Oeser. When his father arranged for him to study law, he followed a procedure that persisted throughout his formative years; for he himself had a strong hand in his own formation. He pursued his “real work” alongside his external obligations, not only with drawing, but with botany, osteology, and the other sciences.

Again, in Oeser’s studio we find the watershed of old and new. Goethe learned the classical laws of painting from plaster casts to experience the movement of light and shade. These in turn were applied to drawing plants and animals from life. It was at Oeser’s that Goethe acquired the habit of carrying a sketchbook wherever he went, drawing the plants of the fields and woodlands.

After leaving the master’s studio, Goethe entered the social circle of a group of pietists and became acquainted with the unique individual, Johann Kaspar Lavater (1741-1801). Lavater shared with Goethe the writings of those Rosicrucian seekers who had fathomed the non-visible secrets of nature. What seemed especially impressive was that the old alchemists realized that by immersing the mind in the transformations witnessed in nature, the perceptual faculties also undergo a transformation, akin to the changes seen in nature. They begin to experience not only events in nature, but also forces.

Goethe became Lavater’s traveling companion and accompanied that loquacious man on a whirlwind lecture tour. During the lectures and afterward, at the inns where they stayed, Lavater articulated his ideas on human physiognomy to the young Goethe. Goethe was impressed by Lavater’s careful study of the changing forms of the human countenance, and by Lavater’s ability to read the soul’s history solely from the shape and contour of the facial features. In his Autobiography Goethe writes more about Lavater and his book Physiognomy than anything else. What he describes about Lavater’s work to some extent applies to his own.

“His Physiognomy rests on the conviction that the sensible corresponds throughout with the spiritual, and is not only an evidence of it, but indeed its representative.”

Lavater pictures the human face as if it were a landscape, which points to another landscape existing in the spiritual, only partly congealed into physical reality. Here is the beginning of such a description (quoted at length by Goethe):

See the blooming youth of twenty-five! The lightly floating, buoyant, elastic creature! It does not lie, it does not stand, it does not lean, it does not fly, it floats or swims. Too full of life to rest, too supple to stand firm, too heavy and too weak to fly.

A floating thing, then, which does not touch the earth! In its whole contour not a single slack line, but, on the other hand, no straight one, no tense one, none firmly arched or stiffly curved: no sharp-entering angles, no rock-like projection of the brow; no hardness; no stiffness; no defiant roughness; no threatening insolence; no iron will, all is elastic, winning, but nothing iron.

This goes on for pages, moving fluidly from feature to quality incredibly mobile; changing forms appearing and receding, until at last the whole person emerges as an image. For Goethe this became a schooling in observation, how the myriad details of the face are animated by and inseparable from spiritual forces. For in the human countenance the physical forms and the higher being are in constant interplay. Goethe’s long acquaintance with Lavater stands at the root of his penetration of the “archetypes” within nature. He was stimulated by Lavater’s energy (he had more fire, according to Goethe, than any person he had ever met) but he was repelled by Lavater’s religious fanaticism. Goethe preferred to extract the spiritual archetype which appeared to him actually entwined in nature’s forms.

For Goethe it could not be true to impose a spiritual interpretation from outside. Such an archetype would be most alive at the moment of encounter. Its continued reality depended upon enhanced powers of perception. It was in this sense that Goethe considered himself “a child of this world.” (In a humorous poem of this period, Goethe pictures himself happily devouring a salmon while Lavater runs full-tilt at Revelation!).

After a number of years of intense literary activity, Goethe, at the age of 26, was appointed to be director of the School of Mines in the Duchy of Weimar. There and in subsequent trips to the Harz Mountains and Alps, Goethe was stimulated to read the features of the face of the earth and to regard them as a kind of script that could be learned, if only sufficient effort was made. He took copious field notes and tried to re-create in his mind the many changes he observed in geological strata. In 1785 he travelled through the Harz Mountains to study what works with tremendous power on the various forms of granite. He was accompanied by the artist George Kraus who made wonderful geological drawings for him as they travelled. He relates this experience in a passage from his unfinished Novel of the Universe.

“Every excursion into the unknown mountain regions confirmed earlier experience, that the granite was the highest as well as the deepest rock formation; it confirmed that this stone was the primal foundation of our earth. Its mixture, manifold and yet uniform, varies in innumerable ways. The position and relationship of its parts, its durability, its color all differ in each mountain range. Also the masses of each single mountain change from step to step, and yet if viewed as a whole are ever the same. Sitting on a high bare summit and surveying the wide landscape, I may say to myself: Here you are resting directly on a foundation which reaches down to the deepest layers of the earth. These summits which surround me have produced nothing living and have devoured nothing living. They are before all life and above all life. At this moment when, as it were, the inner earth forces of attraction and motion affect me directly and the heavenly influences soar closer to me, I become attuned to a higher observation of Nature. I survey the world–its rugged or softer valleys my soul is lifted above itself and all other things. It longs for the nearness of Heaven. Prepared by such thoughts, the soul penetrates into past centuries. It recalls the geologic observations of past careful observers, the conjectures of fiery spirits about the primal conditions. This cliff, I say to myself, jutted upward to the clouds in a more rugged indented form, when this summit stood as a sea-girt island among the ancient waters. Around this cliff stood the Spirit who was brooding above the waves. Out of their wide womb the higher mountains were formed from the fragments of primeval rocks. And in their turn, the fragments of those wave-born mountains and the remnants of the creatures inhabiting them formed the later more distant mountain ranges. Now the moss begins to sprout. The shell enclosed ocean creatures diminish. the water sinks down. The mountains become verdant and everything begins to teem with life.”

Later in Wilhelm Meister Goethe describes these youthful intimations of a “primal condition” as the beginning of a legible script.

“But if I just used these fissures and crevices as letters of an alphabet, had to decipher them, formed them into words and learned to read them easily, would you have anything to say against this?”

Like his contemporaries, Goethe walked amongst the offspring of creation, observing endless details with great care, but unlike the others, he experienced an “original condition” from which these offspring arose. In an early fragment, he says that nature’s “life is the life of her children,” but “the Mother where is she?”

Expansion and Contraction

As early as 1775 Goethe began an earnest observation of the plant kingdom. City born, bred, and educated, his life suddenly expanded into a new world.

“I had the joy of exchanging the stuffiness of town and study for the pure atmosphere of country, forest and garden.”

Goethe spent much time in the Duchal forests with Johann and Christian Sckell, two brothers who were skilled foresters and horticulturists. With them he began to experience the types of flora which grow out of a particular terrain. In the “History of his Botanical Studies” he writes:

“the rising science of geology was attempting to give an account of the ground and soil upon which these ancient forests had taken root. conifer forests of all kinds with their somber greenness and balsam fragrance, beech groves of more joyful appearance each had sought and won its place Here too we saw the entire family of mosses in greatest diversity. We even studied the roots beneath the soil. For to these forest regions, from remotest times onward, there had been migration of herbalists, who [worked] with secret formulas passed on from father to son. [The] universal reputation of these latter for possessing curative powers was renewed, extended and utilized by assiduous workers called balsam carriers. In these activities the gentian played a big role, and it was a pleasant task to examine closer the plant and flower of this rich genus in its various forms, especially the salutary root. This was the first plant genus to attract me in earnest and later to inspire me to continue my study of its species.”

But just as Goethe’s entrance into nature had been an expansion from his urban background and education, so the Linnaean system of classification seemed to him a confinement at odds with original observation of plant forms. In later years he wrote:

“The variability of plant forms, whose unique course I had long been following, now awakened in me more and more the idea that the plant forms round about me are not predetermined and established; instead we find allotted to them, along with their stubborn clinging to genera and species, a happy mobility and flexibility, enabling them to adapt themselves to many conditions throughout the world which influence them, and to be formed and reformed in accordance with them.”

He stressed this again in his Genesis of the Essay on the Metamorphosis Plants

“I had not ceased to go forward along the path marked by Linne, upon which, however I found a good many things holding me back, if not actually leading me astray I conscientiously attempted to apply botanical terminology to plant parts, but unfortunately was very greatly impeded in the process. For instance, when on the selfsame stem saw what was indubitably a leaf gradually turning into a stipule; when on the selfsame plant discovered first rounded then notched and finally almost pinnate leaves, I lost the courage to drive in a stake or even to draw a line of demarcation.

“I therefore felt justified in concluding that Linne and his successors had proceeded like legislators, less concerned with what is, than with what should be but rather intent upon solving the difficult problem of how so many inherently unfettered beings can be made to exist side by side with a degree of harmony.”

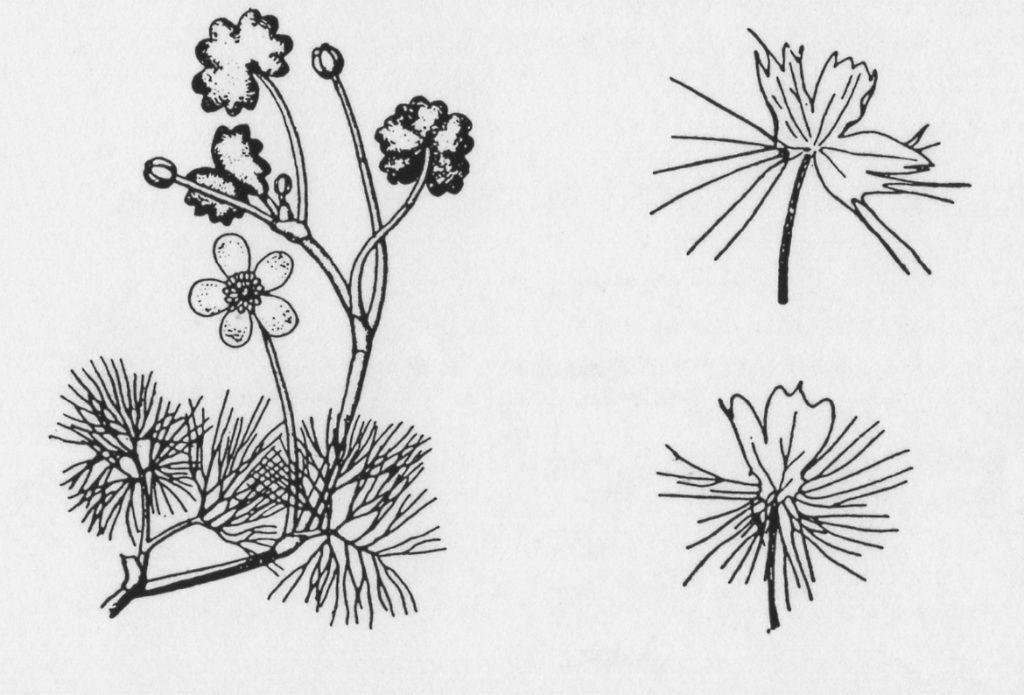

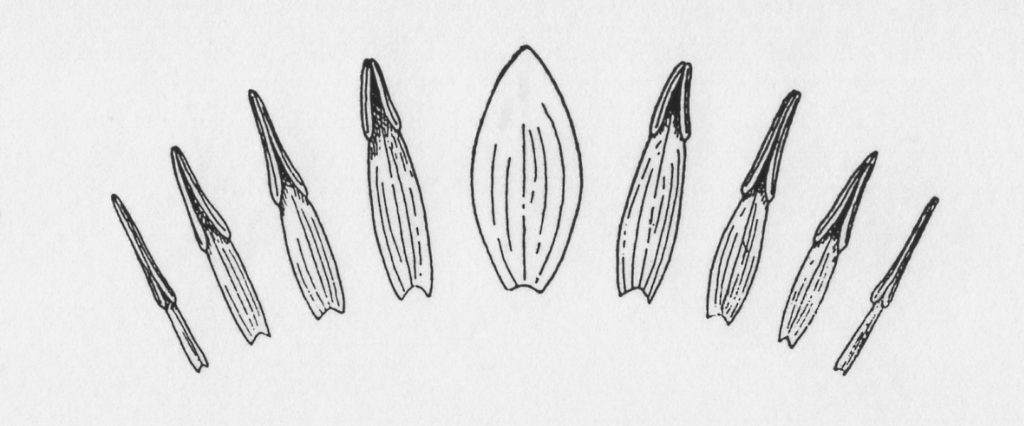

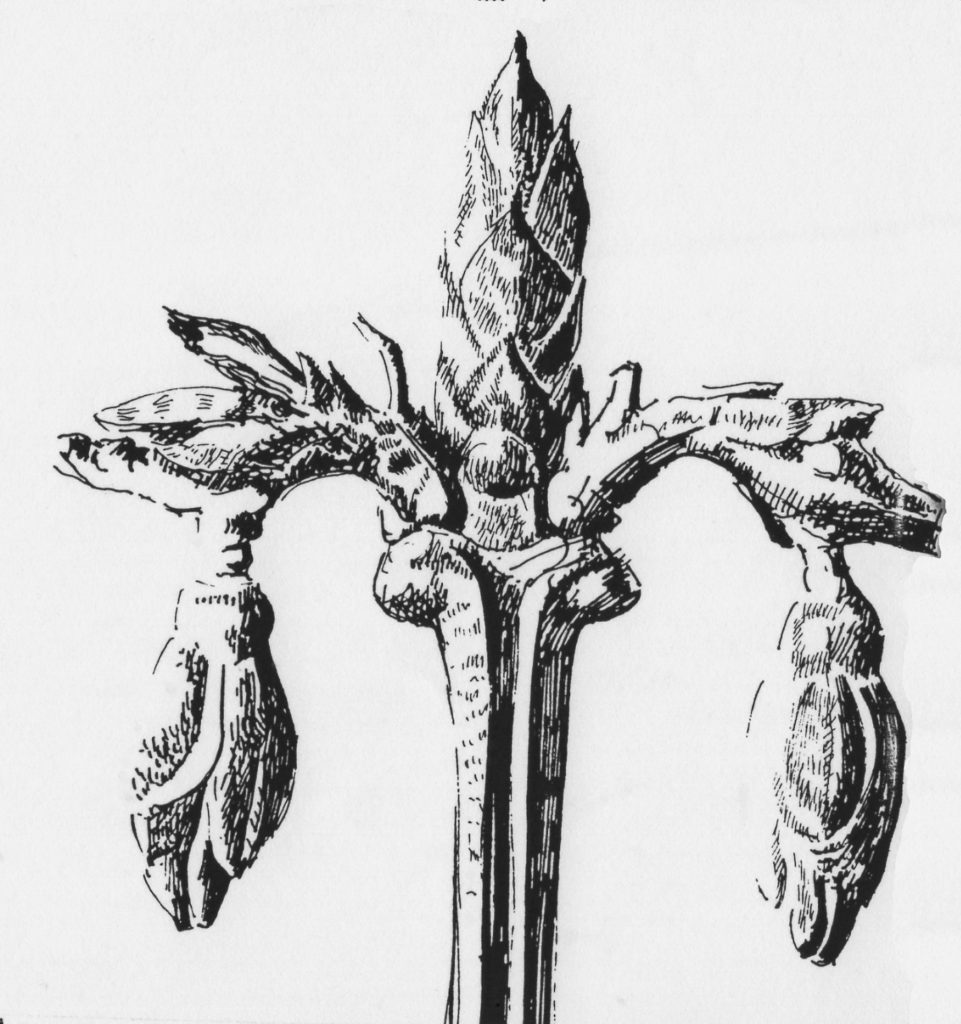

Goethe was less concerned with how plant species appear in a given moment of time than in the transitional states of plant parts (when, for example, a water lily petal becomes a stamen) which offer a cue to the longer process of metamorphosis. This longer process appeared to him as the reality of the plant. It was often more evident in apparent malformations (for example, carnation stamens reverting to petals) than in regular development.

In order to pursue what in his own words was the most exciting discovery of his life, Goethe expanded from the confines of his beloved court of Weimar and travelled to Italy. At the age of 36 he left by night disguised as a Bohemian painter named Moller. He travelled over the Alps to what could only appear to him as a land of dreams, where he was endlessly stimulated by the manifoldness of unfamiliar tropical vegetation.

“The luxuriance of the foreign vegetation impressed me most forcibly when I visited the Padua Botanical Garden, where a broad high wall with the fiery red bells of the Biqnonia grandiflora glowed enchantingly before me.”

The way the simple lanceolate leaves of a fanpalm successively separate seemed to spark in Goethe that insight which he considered the happiest moment of his life. He began to see not only plant parts, but the effect of formative forces. Here, he says:

“I first conceived the idea of plant metamorphosis, pursuing it with joy ecstasy indeed, lovingly immersing myself in it in Naples and Sicily”

He wrote to Herder saying that he felt like the woman in the gospels who was overcome by the joy at finding the silver piece that was lost.

“I traced the variation of all forms as I came upon them. In Sicily, the final goal of my journey, the conception of the original identity of all plant parts had become completely clear to me; and everywhere I attempted to pursue this identity and to catch sight of it again. Only a person who has experienced the impact of a fertile idea will understand what passionate activity is stirred in our minds, what enthusiasm we feel, when we glimpse in advance and in its totality something which is later to emerge in greater and greater detail.”

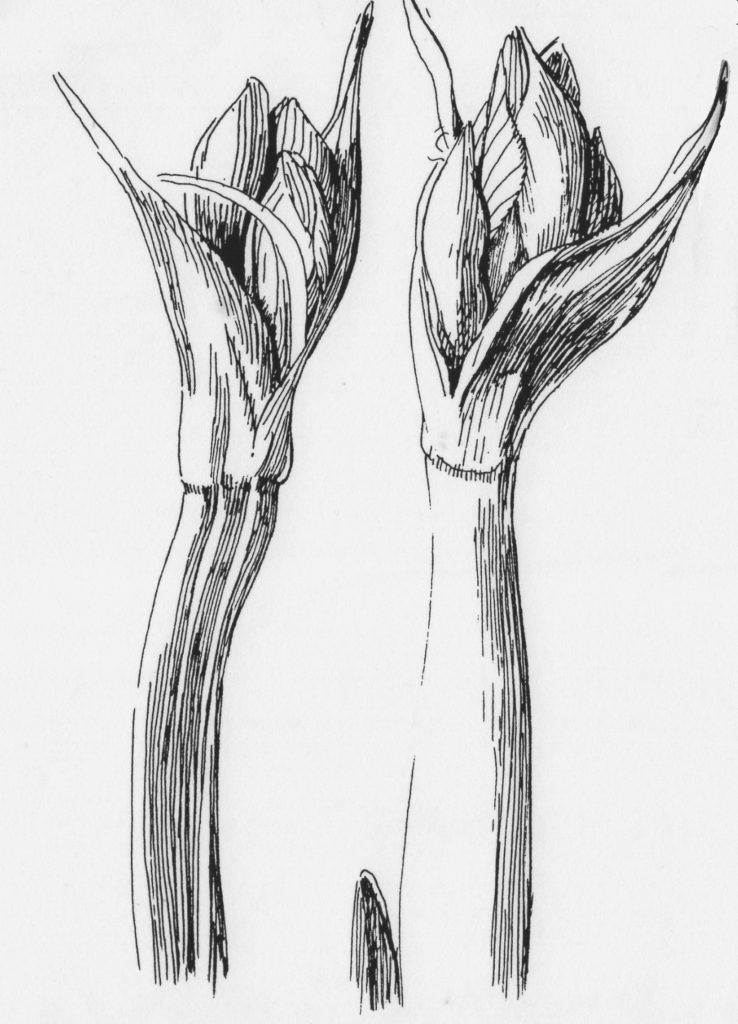

What was unique to this approach was that Goethe observed the plant in its totality in rhythmic sequence of growth. He saw substance appearing and disappearing in a series of expansions and contractions. He noticed leaves expanding and enlarging, then contracting and indenting toward the sepals. He noticed petals expanding and stamens and pistils contracting. He saw fruit enlarging and seed contracting. Moving from one plant genus to another he observed that each of these plant organs was a successive modification of the leaf. Even pods and fruit could be seen as leaf. Through these observations, a picture appeared of the formative forces that do this shaping, diminishing and refining, just as a sculptor removes and shapes substance to create a final image. Within the structure and transformation of the leaf or as Goethe carefully says “which we ordinarily designate as leaf,” lies “the true Proteus who can conceal and reveal himself in all forms.” What hovered in Goethe’s mind at the time and for the rest of his life was “a supersensible plant archetype” unfolding in time “the sensible forms.”

Seeing the Archetype

Goethe was very quick to emphasize as he did to Schiller that the archetype was not an idea. It could be seen in the sequence of forms as a plant develops from seed-leaf to fruit. Only in single, fixed specimens can it not be seen. If one begins to bend one’s mind into the actual movement of growth, this seeing can begin to become second nature. The mind begins to divest itself of some of its greyness, as it experiences the plant in time. Goethe says of his discovery:

“I prided myself on understanding Nature’s method in producing, in accord with definite laws, a living structure that is the model of everything artistic.”

To enable us to enter more fully into Goethe’s method of observation, we can look closely at the special effect that metamorphosis has on the observer Goethe says of himself that “the phenomena of formation and transformation had taken mighty hold” of him, and that nature and the power of imagination were “vying to see which could prevail with greater boldness.” When one actually “does” observation along Goethean lines (see below), it is important to become aware of these effects, just as Goethe himself was. This much we will say now.

How could I recognize this or that plant structure as a plant if they were not all formed in accordance with one pattern?

Goethe’s Diary 1787

The mind’s eye watches and recreates living forms as they flow from the fountain of the meristem, express a particular stage of growth, and then die away behind. By watching not only this process, but also by noticing what effect this observation has on the self, a remarkable insight into the nature of Goethe’s imaginative faculty can arise. When formation and transformation in nature are followed closely and then mentally re-imagined, the observer can discover (it can be a shock!) that he is experiencing something of his own “I” activity. The “I” is not “exercised” in any single stage of growth, but in the entire possibility of grasping and casting off one place of growth and moving to another. Here one can experience first hand the imaginative faculty which is capable of seeing metamorphosis. As was said In the beginning of this essay the imaginative power of metamorphosis can be found in the “act of disappearance itself. In his essay “Formation and Transformation” Goethe quotes this verse from Job:

“Lo, He passes by me

Before I am aware of it,

and is transformed

before I can take hold of it”

A special insight into the world is granted to those who attempt to align themselves, in this way, with the forces of transformation which occur in nature.* Nature’s imagination gradually becomes one’s own. We believe it was in this sense that Goethe asserted late in life:

“I wish it to be wholly understood what I have become to Nature and what Nature has become to me.”

*This thought became the cornerstone for Steiner's development of a Goethean science. In his essay on "The Chemical Wedding of Christian Rosencreutz" Steiner wrote: “the creative activity of nature is guided to awakening the dead cognitional forces to a higher life just as in the green leaf of the plant such a possibility is arrested and yet the formative forces of the plant's growth advance beyond this form, making the colored leaf of the blossom appear at a higher stage, so can man progress from the formation of his forces of knowledge which are directed to what is dead to a higher stage of these forces." (From Allen, A Christian Rosencreutz Anthology, Blauvelt, N.Y ., R. Steiner Pub. 1968))

A Plant Exercise

As an exercise to develop these capacities, plant some seeds of basil between two damp paper towels. When they germinate observe the roots and the first small leaves. Draw a picture of how they appear to you. When they are one inch tall, transplant them into clay pots with garden soil mixed with peat moss or compost. Observe how the leaves change as node after node is produced. Draw the leaf and its accompanying node. Eventually you will see the size of the leaves diminish as the plant approaches flowering. When flowers appear draw them with the aid of a magnifying glass. Put all of these drawings together and you have a time-lapse picture of the plant.

Next, close your eyes and try to visualize the successive stages in the growth of the basil. In your mind allow the seed to sprout and form the first root and leaves. Visualize the shooting of the leaves and the contracting of the nodes into the flower. When this image can be sustained, try to draw the flower purely from memory. If there are any blank spots go back to observing the plant. Once you feel that the basil is living in your imagination, you may wish to go to a botany text to check your picture with the scientific facts.

To go still further find other members of the labiate or mint family, such as spearmint (Mentha spicata). Follow a similar procedure with this family member as you did with basil. Grow, draw and visualize the stages of growth. Through this activity you may begin to experience the archetype of this group of plants. Later on, when imagining these plants, the order of their development will unfold in your imagination exactly as it does in Nature. The key is truthfulness in observation and the willingness to keep an open frame of mind. You will find that after exercises of this kind your powers of observation are enhanced and images come to mind with a force and clarity that is astonishing.

“The entire plant kingdom will appear to us as another tremendous sea which is just as necessary for the conditioned existence of the insects as the oceans and rivers [are] for the fish. We shall see that a tremendous number of living creatures are born and nourished in this plant sea. Indeed, we shall finally regard the entire animal world as only another great element, where one race has its continuation in and from another if not its very origin.”

Goethe

“When we observe such subtle differences [between species of plants] we are using a form of judgement similar to the judgement a painter uses in trying to determine a form or color appropriate for a particular space in painting. The results of such “open” observations allow us to enter into the realm of the imagination.”

D. Klocek

Sources and Further Reading

- Bochemuhl, Jochen, In Partnership with Nature, (Wyoming RI: Bio-Dynamic Literature, 1981)

- Goethe, J.W von, The Autobiography of Goethe, trans. John Oxenford (NY• Horizon Press, 1969)

- Goethe’s Botanical Writings, trans. Bertha Mueller (Honolulu: University of Hawaii, 1952)

- The Metamorphosis of Plants, (Wyoming RI: Bio-Dynamic Literature, 1974)

- Selected Verse, trans. David Luke (Baltimore: Penguin, 1972)

- Wilhelm Meister trans. Carlyle (London: Chapman and Hall, 1824)

- Grohmann, Gerbert, The Plant (London: Rudolf Steiner Press, 1974)

- Koepf and Jolly, Readings in Goethean Science (Wyoming RI: Bio-Dynamic Literature, 1978)

- Magnus, Rudolf, Goethe as a Scientist (NY Collier, 1961)

- Steiner, Rudolf, Goethe the Scientist (NY: Anthroposophic Press, 1950)

- Goethe’s Conception of the World (NY: Anthroposophic Press, 1928)

Many of the plant drawings in this article have been inspired by a wonderful book of photographs called Art Forms in Nature by Karl Blossfeldt (New York: Universe Books, 1967). Highly recommended!

Dennis Klocek is an artist and writer on biodynamic themes living in Carmichael, California. He is the author of The Bio-Dynamic Book of Moons published by Bio-Dynamic Literature. Joel Morrow has written and lectured on Goethean plant morphology for many years.

GOETHE ON NATURE AND INNER DEVELOPMENT NATURE

Nature! We are encompassed and embraced by her powerless to withdraw.

Yet powerless to enter more deeply into her being!

Uninvited and unforewarned,

We are drawn into the circle of her dance,

And are swept along until, exhausted,

We drop from her arms.

She is creating new forms eternally

What is now, has never been;

What has been, will never be again.

She is impatient with anything static, and has set her curse on stagnation.

She is putting on a spectacle,

But whether she is watching it we cannot tell,

But she is producing it for us who stand in the wings.

Since she is always creating new spectators

Her spectacle is forever new.

Life is her finest invention; and her device

For producing an abundance of life

Is her Masterstroke Death.

She is the supreme artist!

With the simplest materials, she creates the most remarkable contrasts.

Seemingly without effort she achieves perfection;

Yet her utmost precision is hidden by softness.

She has pondered deeply and meditates incessantly

Not as human being, but as Nature.

By merely watching her we cannot fathom the mysterious final truth she is withholding.

We live within her yet are foreign to her

Conversing with us endlessly, she never divulges her secret.

She lives only in her children,

Yet where can they find her their mother?

Condensed from a fragment attributed to Goethe.

Dennis Klocek

Dennis Klocek, MFA, is co-founder of the Coros Institute, an internationally renowned lecturer, and teacher. He is the author of nine books, including the newly released Colors of the Soul; Esoteric Physiology and also Sacred Agriculture: The Alchemy of Biodynamics. He regularly shares his alchemical, spiritual, and scientific insights at soilsoulandspirit.com.

2 Comments

Leave a Comment

Similar Writings

The Moral Roots of the Climate Crisis

This is the last chapter in “The Harmonies of Storms” Dennis’ PDF eBook on the Music of the spheres; Harmony in climate change. In his widely acclaimed movie, An Inconvenient Truth, Al Gore concludes that the climate crisis is in reality a moral crisis. Just what does that mean? How is morality, traditionally a soul…

Thanks for sharing your beautiful inspired written piece on Goethe and his immersion in the plant and inner world.

You have written it so well that the text is as alive as Goeths work itself.

Thanks for all your wonderful work Dennis

and you too Ben. So wonderful you two working together

Thanks Peter! It’s a good one, isn’t it?! It brings so much of the work together.